Our Research

The overall theme of our lab is the regulation of energy homeostasis in mammalian systems, with special reference to adipose and muscle tissues. While we have long been interested in diabetes and obesity, our current interests extend to muscle disorders, neurodegeneration and cancer cell metabolism. We are particularly interested in mitochondrial metabolism in these disorders and in the development of novel therapeutic approaches. We work at both the biochemical and physiological levels, employing cultured cells and in vivo murine models.

The following are current research areas:

The following are current research areas:

PGC1α and the control of energy homeostasis

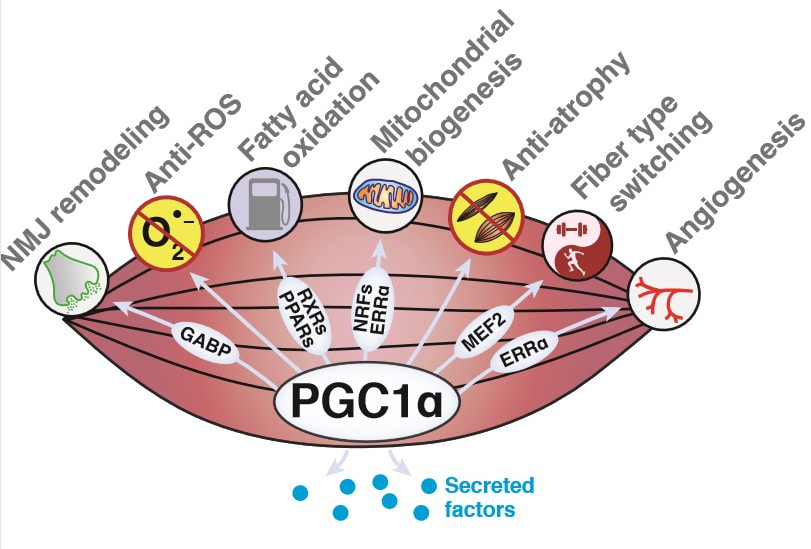

We discovered the transcriptional coactivator PGC1α in 1998 [1]. Work from our lab and others has demonstrated that this molecule is a dominant regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis in most tissues and is conserved from humans to flies. Complex regulation of PGC1α and its multiple isoforms allows it to control not only cellular mitochondrial levels, but also tissue-specific mitochondrial functions [2]. These features of PGC1α enable animals to adapt their energy metabolism to dynamic environmental and nutritional settings. We are currently taking biochemical, genetic, and evolutionary approaches to explore new modes of PGC1α regulation, including regulation of mRNA translation as well as post-translational modification of the protein itself [3].

We discovered the transcriptional coactivator PGC1α in 1998 [1]. Work from our lab and others has demonstrated that this molecule is a dominant regulator of mitochondrial biogenesis in most tissues and is conserved from humans to flies. Complex regulation of PGC1α and its multiple isoforms allows it to control not only cellular mitochondrial levels, but also tissue-specific mitochondrial functions [2]. These features of PGC1α enable animals to adapt their energy metabolism to dynamic environmental and nutritional settings. We are currently taking biochemical, genetic, and evolutionary approaches to explore new modes of PGC1α regulation, including regulation of mRNA translation as well as post-translational modification of the protein itself [3].

|

We are also interested in PGC1α function in the context of exercise. PGC1α is induced in muscle upon exercise and its forced expression in this tissue is sufficient to confer many of the beneficial effects of exercise, including effects on distant tissues [4]. We are therefore interested in using models of elevated PGC1α as a discovery tool to identify secreted factors that mediate the effects of exercise on tissues including muscle, fat, bone, and brain.

1. Puigserver, P., et al., A cold-inducible coactivator of nuclear receptors linked to adaptive thermogenesis. Cell, 1998, 92(6):829–839.

2. Ruas, J. L., et al., A PGC-1α isoform induced by resistance training regulates skeletal muscle hypertrophy. Cell, 2012, 151(6):1319–1331. 3. Dumesic, P. A., et al., An evolutionarily conserved uORF regulates PGC1α and oxidative metabolism in mice, flies, and bluefin tuna. Cell Metabolism, 2019, 30(1):190-200. 4. Lin, J., et al., Transcriptional co-activator PGC-1 alpha drives the formation of slow-twitch muscle fibres. Nature, 2002, 418(6899):797–801. |

Creatine futile cycle and metabolism

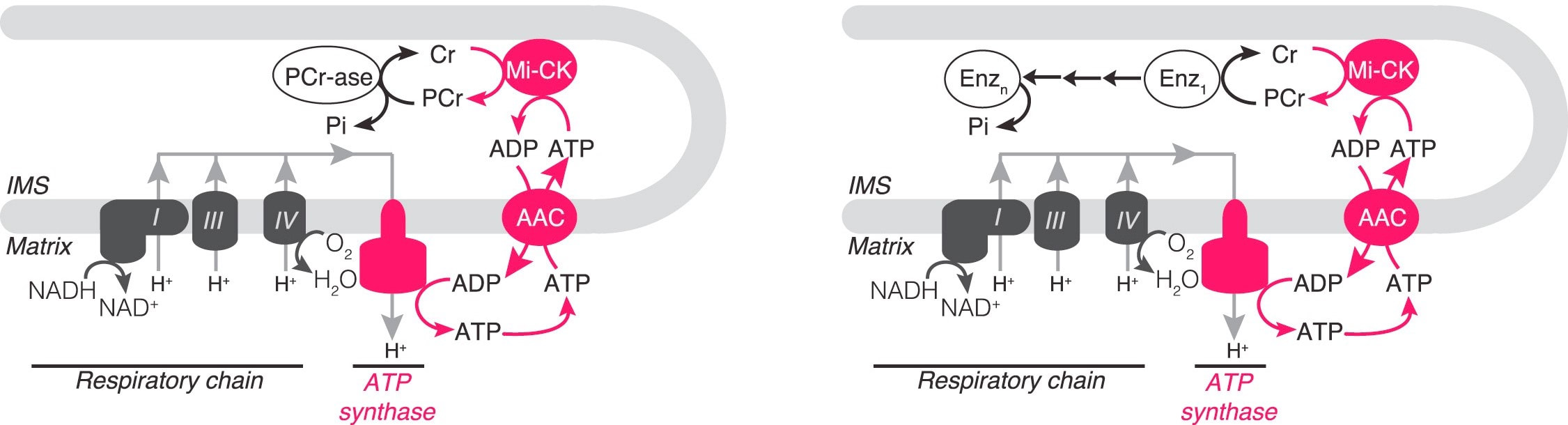

We have described a pathway, originating from our unbiased proteomic work, in which creatine and phosphocreatine are in a futile cycle, dissipating the high energy charge of phosphocreatine, without performing any mechanical or chemical work. Like UCP1, this pathway is downstream of the canonical adrenergic signaling pathway in thermogenic fat [1]. Critically, we have provided biochemical, pharmacological and genetic evidence that this pathway is a major component of adipose tissue thermogenesis [1,2,3]. Currently, we seek to answer critical questions about the futile creatine cycle regarding biochemical steps in this pathway that are still not understood. Additionally, we will determine, using genetic tools, the contributions made by this cycle to whole body energy expenditure, under a variety of physiological conditions experienced by both mice and humans.

We have described a pathway, originating from our unbiased proteomic work, in which creatine and phosphocreatine are in a futile cycle, dissipating the high energy charge of phosphocreatine, without performing any mechanical or chemical work. Like UCP1, this pathway is downstream of the canonical adrenergic signaling pathway in thermogenic fat [1]. Critically, we have provided biochemical, pharmacological and genetic evidence that this pathway is a major component of adipose tissue thermogenesis [1,2,3]. Currently, we seek to answer critical questions about the futile creatine cycle regarding biochemical steps in this pathway that are still not understood. Additionally, we will determine, using genetic tools, the contributions made by this cycle to whole body energy expenditure, under a variety of physiological conditions experienced by both mice and humans.

1. Kazak, L., et al., A creatine-driven substrate cycle enhances energy expenditure and thermogenesis in beige fat, Cell, 2015, 163(3):643-655.

2. Kazak, L., et al., Genetic Depletion of Adipocyte Creatine Metabolism Inhibits Diet-Induced Thermogenesis and Drives Obesity, Cell Metabolism, 2017, 26(4):660-671.

3. Kazak, L., et al., Ablation of adipocyte creatine transport impairs thermogenesis and causes diet-induced obesity, Nature Metabolism, 2019, 1:360-370.

2. Kazak, L., et al., Genetic Depletion of Adipocyte Creatine Metabolism Inhibits Diet-Induced Thermogenesis and Drives Obesity, Cell Metabolism, 2017, 26(4):660-671.

3. Kazak, L., et al., Ablation of adipocyte creatine transport impairs thermogenesis and causes diet-induced obesity, Nature Metabolism, 2019, 1:360-370.

|

Irisin and its roles in metabolism and skeletal remodeling

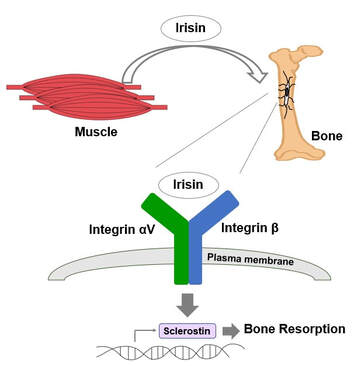

Exercise is crucial to prevent obesity, diabetes, fatty liver disease and osteoporosis. These beneficial effects are partially mediated by myokines, hormone-like molecules produced by skeletal muscle. Irisin is a myokine which is a cleaved product from fibronectin type III domain-containing protein 5 (FNDC5) and is shed into the intracellular milieu and blood to reach other organs [1]. Irisin circulates at 3-5 ng/ml in human plasma and exercise increases the concentration [2]. Previously, we reported that irisin treatment increases thermogenic gene expression in subcutaneous fat [1] and the expression of a potential neuroprotective gene in the brain [3]. It also increases both osteocytic survival and production of sclerostin, a local modulator of bone remodeling, and stimulates osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption [4, 5]. Genetic ablation of FNDC5/irisin completely blocks osteocytic osteolysis and bone resorption induced by ovariectomy, preventing bone loss [4]. Furthermore, we determined that the αV class of integrins serve as irisin receptors mediating effects in bone and fat [4]. Currently, we are testing therapeutic effects of irisin in osteoporosis. We are also exploring new roles of irisin in neurodegeneration such as Alzheimer’s disease and Amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS). 1. Boström, P., et al., A PGC1-α-dependent myokine that drives brown-fat-like development of white fat and thermogenesis. Nature, 2012, 481(7382):463-468. 2. Jedrychowski, M., et al., Detection and Quantitation of Circulating Human Irisin by Tandem Mass Spectrometry. Cell Metabolism, 2015, 22(4):734-740. 3. Wrann, C., et al., Exercise induces hippocampal BDNF through a PGC-1α/FNDC5 pathway. Cell Metabolism, 2013, 18(5):649-659. 4. Kim, H., et al., Irisin Mediates Effects on Bone and Fat via αV Integrin Receptors. Cell, 2018, 175(7):1756-1768. 5. Estell, E., et al., Irisin directly stimulates osteoclastogenesis and bone resorption in vitro and in vivo. eLife, 2020, 9:e58172 |

PPARγ in cancer biology and cancer treatment

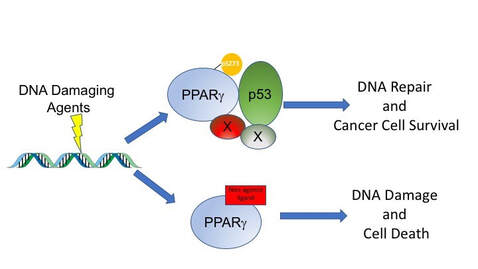

There is increasing interest in the overlap between obesity, diabetes and cancer, which has led to interest in exploring the role of therapeutics for metabolic disease in cancer treatment [1]. We have shown, over many years, that drugs that modulate PPARg can slow down the growth of tumor cells in vitro and in mouse models of cancer [2, 3]. More recently we have shown that PPARg ligands can synergize with cytotoxic therapies to increase DNA damage accumulation and cell death [2,4-6]. We are trying to understand the mechanisms of these striking effects and how this can be leveraged in human cancers.

There is increasing interest in the overlap between obesity, diabetes and cancer, which has led to interest in exploring the role of therapeutics for metabolic disease in cancer treatment [1]. We have shown, over many years, that drugs that modulate PPARg can slow down the growth of tumor cells in vitro and in mouse models of cancer [2, 3]. More recently we have shown that PPARg ligands can synergize with cytotoxic therapies to increase DNA damage accumulation and cell death [2,4-6]. We are trying to understand the mechanisms of these striking effects and how this can be leveraged in human cancers.

1. Khandekar, M.J., et al., Molecular mechanisms of cancer development in obesity, Nature Reviews Cancer, 2011, 11(12):886-895.

2. Mueller, E., et al., Terminal differentiation of human breast cancer through PPAR gamma, Molecular Cell, 1998, 1(3):465-470.

3. Sarraf, P., et al., Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPARgamma, Nature Medicine, 1998, 4(9):1046-1052.

4. Girnun, G.D., et al., Regression of drug-resistant lung cancer by the combination of rosiglitazone and carboplatin, Clin Cancer Res, 2008, 14(20):6478-6486.

5. Girnun, G.D., et al., Synergy between PPARgamma ligands and platinum-based drugs in cancer, Cancer Cell, 2007, 11(5):395-406.

6. Khandekar, M.J., et al., Noncanonical agonist PPARγ ligands modulate the response to DNA damage and sensitize cancer cells to cytotoxic chemotherapy, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2018, 115(3):561-566.

2. Mueller, E., et al., Terminal differentiation of human breast cancer through PPAR gamma, Molecular Cell, 1998, 1(3):465-470.

3. Sarraf, P., et al., Differentiation and reversal of malignant changes in colon cancer through PPARgamma, Nature Medicine, 1998, 4(9):1046-1052.

4. Girnun, G.D., et al., Regression of drug-resistant lung cancer by the combination of rosiglitazone and carboplatin, Clin Cancer Res, 2008, 14(20):6478-6486.

5. Girnun, G.D., et al., Synergy between PPARgamma ligands and platinum-based drugs in cancer, Cancer Cell, 2007, 11(5):395-406.

6. Khandekar, M.J., et al., Noncanonical agonist PPARγ ligands modulate the response to DNA damage and sensitize cancer cells to cytotoxic chemotherapy, Proc Natl Acad Sci USA, 2018, 115(3):561-566.